In the heart of Soweto, the birthplace of South African democracy has been burned, looted and stripped for parts.

Almost 70 years ago, in the early days of apartheid, more than 3,000 people gathered in a dusty square to draw up the Freedom Charter, demanding a series of rights and proclaiming that South Africa “belongs to all who live in it, black and white”.

When apartheid ended in 1994 and Nelson Mandela was elected president by a landslide, the charter became the foundation for the country’s optimistic new constitution. So it made sense, 50 years on, to mark its anniversary and turn this square in the Kliptown area of Soweto into a place that represented the new South Africa.

There would be shops and offices, a museum, a monument to freedom. To top it off, a new hotel opened, marketed as “the first four-star luxury hotel offering African hospitality in the heart of Soweto”. A flame of freedom was lit, surrounded by the words of the charter.

South Africa then was on the up. New homes had been built, and access to electricity and water extended across the country. While much of the country’s wealth still rested in a few white hands, a black middle class was growing and South Africa was preparing to host the football World Cup.

But if the first 15 years of democracy was a success, the same cannot be said for the last 15 years. And the impact can be seen vividly in the square where modern South Africa was born.

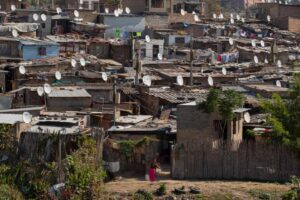

As South Africa prepares to go to the polls on Wednesday, 30 years on from the first democratic elections, it is a nation in crisis. It’s the most unequal country in the world and among the most dangerous. The economy is stagnant, with almost zero growth in a decade and nearly half of adults are out of work.

Basic public services are falling apart. In many parts of the country there is no clean water, while rolling power cuts have become a regular feature of daily life. The government proudly points out it has been 55 days since the electricity went off, a streak that the more cynical expect to last until election day but not much longer.

At the heart of it all is corruption. What was a minor issue under Mandela and his successor Thabo Mbeki exploded when Jacob Zuma came to power in 2009. By the time he was kicked out of office by the African National Congress (ANC) in 2018, billions was looted from the state, leaving almost every part of it bankrupt, from the national airline to the agency that ran the railways.

“The tax authority was effectively taken over by a syndicate of criminals,” says Anthony Butler, a professor of politics at the University of Cape Town. “It’s proved to be very difficult to rebuild those institutions.”

An inquiry into what became known as “state capture” concluded that “the ANC under Zuma permitted, supported and enabled corruption”, though Zuma himself denies any direct role in corruption.

After Zuma, the ANC tried to turn the page, choosing a former Mandela ally, Cyril Ramaphosa, as the new president. Despite admitting his party “made mistakes”, Ramaphosa has been unable to change the country for the better and is now haunted by the ghosts of the ANC past.