Love it or loathe it, there’s no question that Last Night of the Proms operates as an elaborate piece of British cultural theatre, on multiple levels. On the one hand, it’s a rare and exceptionally important opportunity to subvert the sobriety of the classical music establishment. On the other hand, it temporarily legitimises the ecstatic expression of national pride in ways that are profoundly at odds with today’s political climate in the UK.

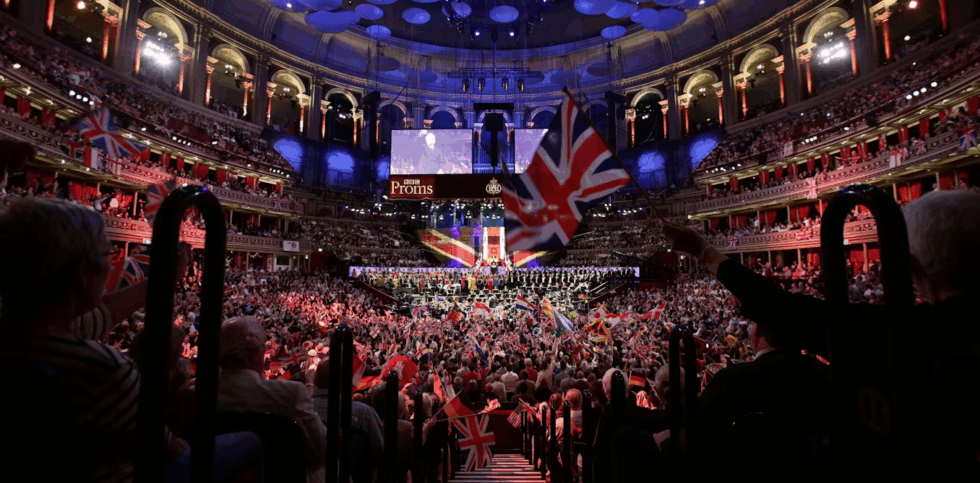

For television audiences and those in the Albert Hall, Last Night of the Proms has become a well-loved communal and carnivalesque celebration. The prim formalities associated with classical music are temporarily upturned. The audience is given the opportunity to “join in” by calling out, whistling, stamping, bobbing up and down, and generally participating.

For a genre where even polite clapping between movements would normally be considered sacrilegious, this level of audience involvement is striking. It’s for this reason that the Last Night of the Proms is often understood by those who actively engage with it as representing the “inclusive” face of classical music.

But musical performance doesn’t happen in a cultural or political vacuum – even where the intended effect is “escapism” from the realities of the outside world. For escapism to work there needs to be a collective recognition of what it is that we’re escaping from.

When Britannia ruled

In Last Night we see a once relatively benign relic that now resonates uncomfortably with contemporary Britain. While the event appears true to the Proms’ late-19th century motives of taking classical music to the masses, it also carries the hallmarks of something that took shape against a backdrop of growing – and state-sanctioned – nationalism.

Its conception intersected with the “first British folk revival” at the turn of the 20th century, during which traditional songs and tunes were being collected from the rural peripheries by educated middle-class scholars and enthusiasts. The aim was to restore the cultural roots of the nation by pressing these rescued antiquities into service as inspiration for a newly patriotic generation and a distinctively British orchestral tradition.

This context is most obvious in Henry Wood’s centrepiece for the Last Night, the Fantasia on British Sea Songs. Growing concerns were developing around the need to articulate and celebrate national identity – and both the folk revival and the Proms were responses to that same impulse.

Some elements of that context feel uncomfortably familiar when looking at Last Night’s idiosyncrasies in 2019. The implications of Brexit —- alongside slow-burn discontent around immigration and globalisation —- have meant that debates about the presence, absence, meanings and significance of national identity are returning to fever pitch.

Nationalism and diversity

If we are to portray (as many less supportive onlookers do) the event to be an object lesson in flag-waving, escapist expressions of national identity, we could also reflect on the fact that this is not necessarily a bad thing. Most cultures around the world have events serving roughly equivalent functions (although normally commemorating historical events, such as Independence Day and Thanksgiving celebrations in the US, or focusing on local vernacular traditions, as in national folk festivals and competitions). While nationalism is undoubtedly a potentially divisive and dangerous force within any society, celebrations of national identity deserve balanced consideration.

But there are nonetheless questions to answer about the appropriateness of a state-funded festival continuing to sanction and celebrate naked statements of British – or is it English? – supremacy (Land of Hope and Glory, Rule Britannia, etc.) with unquestioning jollity during a moment of political crisis, increasing national division, racial tensions and rising xenophobia.